4 Financial Skills That Matter More Than Strict Budgeting

Four practical financial skills that help people stay steady when strict budgets fall short, from calm adjustment to better prioritisation, flexibility, and spending review.

4 Financial Skills That Help When Strict Budgeting Doesn’t Work

Strict budgeting is often cited as the key to good money management. It is seen as a sign of discipline, maturity, and control. For some families, a strict budget can be a powerful way to create stability and structure, especially if there has been a lack of consistency and clarity in how money has been spent in the past.The problem with strict budgeting, though, is that it is not always the best way to achieve sound long-term money management. The truth is, many people can follow their budgets to the letter—until life gets in the way. A bill changes, a work schedule shifts, a family commitment arises, or an unexpected expense occurs. At that point, good money management is no longer about how well a plan was followed, but about how well one can adapt when the plan no longer works.This is why some money management skills are more important than strict budgeting. They are not a shortcut or a substitute for responsibility. Rather, they are useful skills that help people remain steady even when conditions are not ideal. These skills are what will make the difference between a family that feels financially shaky and one that feels financially sound, even if they are making the same amount of money.The following are four money management skills that are always more important than strict budgeting. They are based on real-world behaviour, real-world patterns, and the kind of insight that comes from experience rather than education.1. The Skill of Adjusting Without Overreacting

Many financial issues are exacerbated by overcorrection. A budget is broken, and the reaction is to overcorrect. People try to “solve” the problem by being draconian about spending, setting unreasonably high savings targets, or simply refusing to spend money on anything but the bare essentials for a period of time. This behaviour may feel responsible at the time, but it is rarely sustainable.The more useful skill is adjustment. Adjusting without overcorrecting means recognising that a budget is a tool, not a test of personal willpower. It means reacting to change with subtle, controlled movements rather than drastic ones.For instance, if one area of spending increases—perhaps the cost of groceries goes up or a bill suddenly jumps unexpectedly—adjusting to the change may simply mean cutting back in other areas for a short time. It may mean putting off a non-essential purchase or rescheduling a payment. The goal is balance, not punishment.This is particularly important when expenses are variable, such as household power costs. A budget may be drawn up assuming a fixed monthly amount, but actual bills fluctuate with weather, usage patterns, and pricing changes. Without the skill of adjustment, this means frustration or panic. With the skill, variability becomes something to be managed, not feared.This is one of the main ways that budgeting as a skill differs from budgeting as a process. The numbers themselves are not the problem. The skill of adjustment is what solves the problem.2. The Ability to Prioritise Based on Impact, Not Preference

3. Financial Flexibility as a Practical Tool, Not a Personality Trait

Some people think they are “just not good with budgets” because they find it difficult to stick to a strict plan. The problem is not necessarily that they are irresponsible, but that they are too rigid. A strict plan is great for regular tasks, but it is not very good at handling real life when it becomes unpredictable.This is why financial flexibility is such a valuable skill. It is not a personality type or an attitude. It is the skill of keeping the budget system working even when life gets unpredictable.Flexibility appears in small budgeting decisions. It is the capacity to reorganise spending without getting off track. It is understanding when to hold back non-essential spending, when to rely on smaller cushions, and when to contract further without falling apart into extreme conservatism.In well-managed households, flexibility will often appear as nothing out of the ordinary. It may involve deliberately keeping a few areas of spending underfunded so there is some leeway. It may involve setting expectations based on a realistic month rather than an optimal one. It may involve considering savings goals as flexible rather than fixed, so that progress can continue at a steady rate.Where flexibility is present, budgets can be made more robust. Where flexibility is lacking, budgets are likely to be brittle. In the world as it is, brittleness is what causes trouble.4. The Habit of Reviewing What Is Actually Happening

Practical Financial Skills That Build Adaptability, Resilience, and Better Decision Quality

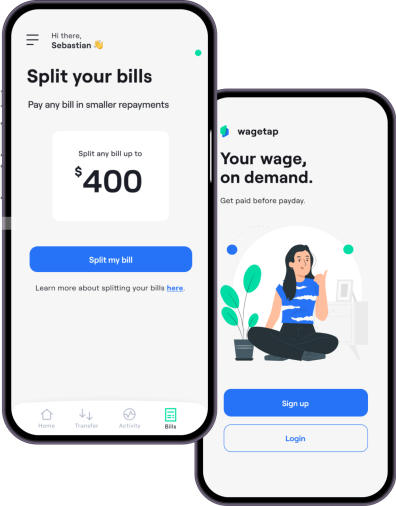

Practical financial skills are important because they function when life gets complicated. Good budgets are great, but they are only as good as reality is to the budget. Skills, however, translate from situation to situation.Adaptability enables individuals to respond without falling apart in overreaction. Resilience enables households to withstand disruption without suffering long-term consequences. The quality of decision-making is enhanced when decisions are made in the context of consequences and awareness rather than in the context of urgency and emotion.For households that budget well but sometimes struggle with the timing of expenses and income, flexible choices may help. Services such as Wagetap, which give households access to their earned income before the regular pay period, may help them get a break when things are tight. This can help individuals keep their cool and think before acting in reactive ways.Ultimately, the aim is not to budget perfectly. Resilience comes from what happens when the budget is pushed to its limits. In real-world finances, the best households are not necessarily those that budget perfectly but those that have the skills to keep moving forward when things change.App StoreGoogle PlayFor additional help in improving your spending habits, you can always download Wagetap. It is a leading wage advance and bill split app that allows you to access your pay early. Emergencies can always happen and Wagetap can help you handle life's unexpected expenses.

Share this post

Download Wagetap today

Get your Pay On demand with Wagetap

Subscribe to our Newsletter

© 2026 Wagetap All rights reserved

Digital Services Australia V Pty Ltd